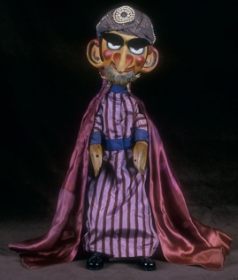

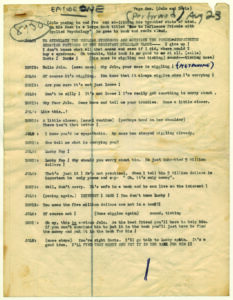

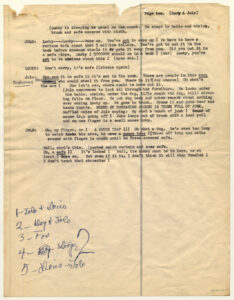

The show’s genial human host, Doris Brown, and a puppet clown named Jolo introduced each episode, promoted sponsors' products, read viewers’ letters on the air, announced the availability of ancillary materials (such as photographs of the puppets that cost 15 cents each), and advertised public appearances.

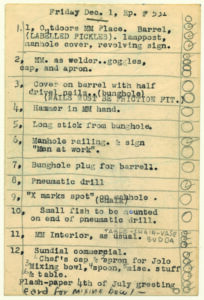

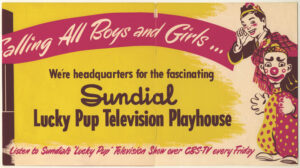

The primary commercial sponsors of Lucky Pup were Bristol-Myers’ Ipana toothpaste and Sundial Shoes. In the early days of television, product advertisements were integrated into the shows rather than promoted during commercial breaks. When Ipana toothpaste became a sponsor of Lucky Pup in March 1949, the Bunins added a toothy puppet character named Smiley to interact with Doris Brown and Jolo the Clown during opening and closing segments.

Foodini Finds an Audience

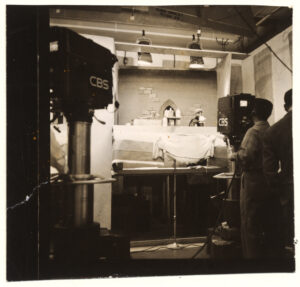

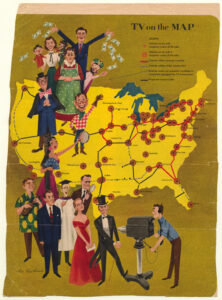

Lucky Pup was propelled by television’s meteoric rise in the post-WWII era. With coaxial cable lines linking New York to Chicago in 1948, and New York to California in 1950, live broadcasts of Lucky Pup could reach viewers coast to coast.

The primary commercial sponsors of Lucky Pup were Bristol-Myers’ Ipana toothpaste and Sundial Shoes. In the early days of television, product advertisements were integrated into the shows rather than promoted during commercial breaks. When Ipana toothpaste became a sponsor of Lucky Pup in March 1949, the Bunins added a toothy puppet character named Smiley to interact with Doris Brown and Jolo the Clown during opening and closing segments.

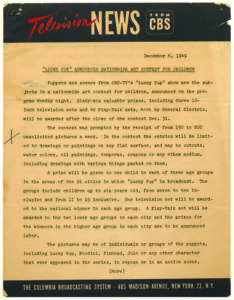

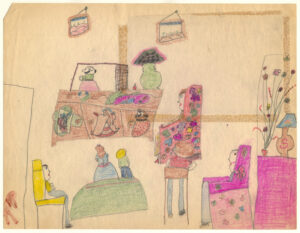

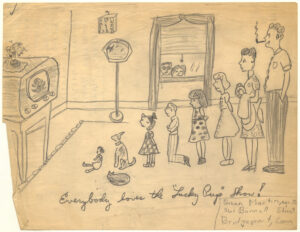

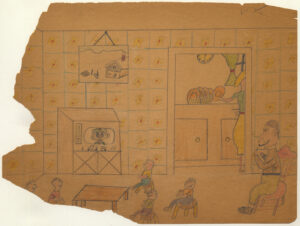

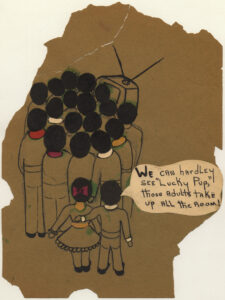

CBS regularly used marketing gimmicks to keep Lucky Pup viewers engaged. One such effort was a contest inviting children to submit a drawing inspired by the program, which elicited more than 14,000 entries. A striking number of the drawings that the Bunins saved for their archive depict families clustered around a television set in a living room, reflecting not only enthusiasm for the characters but also the novelty and communal joy of watching television. Also notable is the real or idealized nuclear family life represented in the drawings.

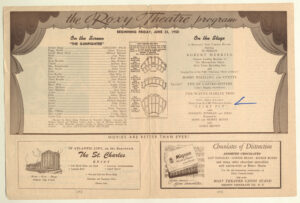

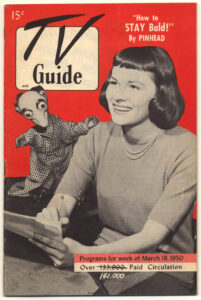

Some worried whether Lucky Pup—with its “evil” protagonist, Foodini —was appropriate for young viewers. In his January 30, 1949 column in the New York Times on the need for standards in television programming, television critic Jack Gould censured Lucky Pup for Foodini’s “plotting,” “trickiness,” and excessive violence toward Pinhead, declaring that the show “comes perilously close to becoming a ‘horror’ item.” The same article claims that “there is no way whatsoever for the public to know in advance what kind of entertainment he is going to see. It must rely solely on the good sense of the television industry and those who work in it.” This, in fact, was untrue in the case of CBS’s presentation of Lucky Pup: before airing at a family-friendly 6:30pm, the show was “previewed” for adult audiences for two weeks at 8:30, presumably past most children’s bedtime.

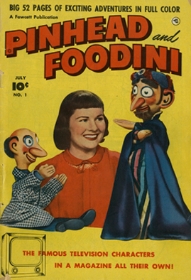

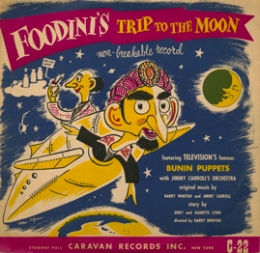

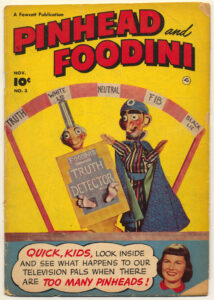

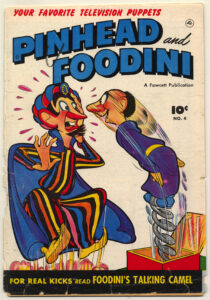

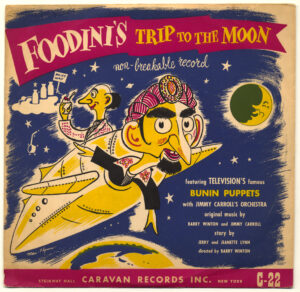

Foodini for Sale

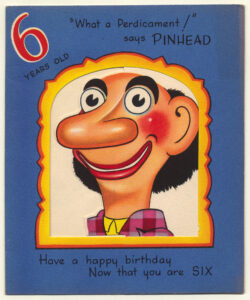

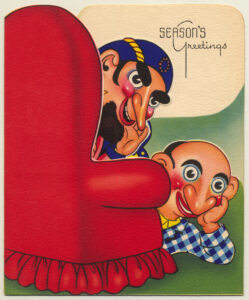

By 1949, images of television stars began to grace all kinds of merchandise, in much the same way as film stars had since the 1910s. While the licensing juggernauts Howdy Doody and Hopalong Cassidy led the way, there was a wide variety of objects available in stores and via mail order that featured characters from Lucky Pup, most often Foodini, Pinhead, and Jolo the Clown, including greeting cards, records, toy puppets, clothing, comic books, jewelry, puzzles, and children’s furniture.

In addition to the licensed merchandise, Sundial Shoes and Ipana offered such promotional items as crystal ball rings, magic tricks, jigsaw puzzles, and paper dolls.

By June 1951, Ipana executives were dissatisfied with CBS’s promotion of Lucky Pup and brought their business—and the show—to ABC. The title was changed to Foodini the Great, and it ran as a weekly, half-hour series on Saturday mornings at 11am. Host Doris Brown retired when she was about to get married (a development she announced on the final Lucky Pup episode on CBS), and was replaced by Ellen Parker and, a few months later, Lou Prentiss. While Saturday morning would soon become prime-time for children’s programming, in 1951 it attracted less overall viewers than the weekday evening hours. The time slot switch and the change in format from a 15-minute to a half-hour show are among the reasons for the show’s cancellation after a mere six months on ABC.

After two years of reruns, Foodini the Great disappeared from the airwaves. Despite their enormous popularity in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Foodini, Pinhead, and friends have been largely forgotten, residing mostly in the nostalgic corners of the internet, where there is still some traffic in Foodini merchandise. MoMI’s comprehensive collection is a powerful reminder of the status of the Bunin puppets as early TV stars, and how much they meant to the emerging medium’s earliest fans. It also points to the ease and eagerness with which American audiences embraced a comic, fictional character who embodied pernicious, stereotyped ideas about “Eastern” people and culture.