The Astoria Studio: From Paramount to KAS

The Astoria Studio has been at the heart of filmmaking in New York City since 1920, with a fascinating history integral to the origin of Museum of the Moving Image. A New York City landmark, the Astoria Studio, which celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2020, is the country’s first motion picture studio to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, cited for its architectural significance and its extensive role in the history of American cinema.

Known affectionately as “The Big House” by three generations of filmmakers because of its monumental main stage, the Astoria Studio was opened by Famous Players-Lasky (later Paramount) in 1920 as its East Coast production center. Such stars as Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson, and W. C. Fields brought glamour to its stages in the silent film era. The Marx Brothers and Claudette Colbert made their first talking pictures there after the Studio’s transition to sound. Over the decades, the Studio complex expanded steadily into the residential streets adjacent to its main building, eventually covering more than five acres. With Paramount’s departure in 1932, the Studio became a rental facility until the U.S. Army purchased it in 1942, turning the site into a center for military motion picture production and distribution for the next 30 years. After falling into disrepair in the early 1970s, a unique public/private partnership transformed the ailing studio complex, leading to the establishment of Kaufman Astoria Studios and to the founding of Museum of the Moving Image. Since its revival, the Studio has thrived, providing stages for such films as The Age of Innocence, Scent of a Woman, The Bourne Ultimatum, and The Irishman, and a home for the production of such television shows as Orange Is the New Black, The Affair, and Sesame Street.

Using film stills, behind-the-scenes photographs, oral histories, posters, and other artifacts from MoMI’s permanent collection, this MoMI Story explores five eras of the Studio’s history, shining a light on the filmmakers, actors, and craftspeople who worked in front of the camera and behind the scenes at the Astoria Studio. Read the history of the studio below to better understand how this storied complex in Queens has remained a vital site of filmmaking from the silent era through the digital streaming revolution.

Paramount: The Silent Years (1920–1927)

In 1920, Famous Players-Lasky (later known as Paramount) combined its four film laboratories and five stages across New York and New Jersey into a single studio complex in the residential neighborhood of Astoria. Its convenient location a few blocks from the elevated subway line (opened in 1917) meant that the hundreds of daily workers needed to operate the studio had easy access to cheap and dependable public transportation, while stars and executives enjoyed a short drive over the Queensboro Bridge.

Construction on the Astoria Studio began in May 1919 at Pierce Street and Sixth Avenue, now known as 35th Avenue and 35th Street. It was a two-million-dollar project that would eventually balloon to two-and-a-half (adjusting for inflation, $2 million in 1920 would be $12,890,000 in 2020). Though the Studio’s official opening was announced for December 1920, nine features and a handful of shorts had already been shot by the end of November. In June 1921, Paramount temporarily closed the Studio for cost-cutting measures during a postwar economic depression.

Production resumed in Astoria one year later, and between June 1922 and spring 1927, 103 films were produced at the Studio—forty percent of Paramount’s output during that period. Though tensions had steadily risen between the Studio’s West and East Coast factions, shooting in New York provided temporary solace for such stars as Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino, temporary Hollywood expats who loved the cultural life New York had to offer.

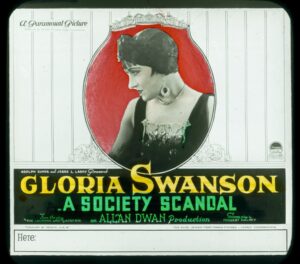

Gloria Swanson

A leading light at Paramount studios, Gloria Swanson was one of the biggest movie stars of the twenties. Nevertheless, she despised Hollywood, and was disdainful of the men in the Los Angeles office. Under the guise of requiring emergency medical treatment, she transferred to the more culturally sophisticated New York, where she felt far more comfortable. “I experienced more art and culture in six months than I had seen in my whole life,” she said after her arrival.

“Every day we all drove across the Queensboro Bridge to the new studio in Astoria in the borough of Queens. It was certainly not another Hollywood. The place was full of free spirits, defectors, refugees, who were all trying to get away from Hollywood and its restrictions. There was a wonderful sense of revolution and innovation in the studio in Queens.”—Gloria Swanson (from Swanson on Swanson, Random House, 1980)

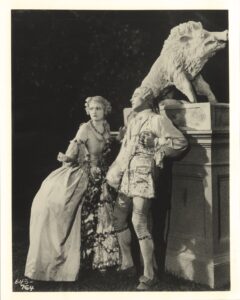

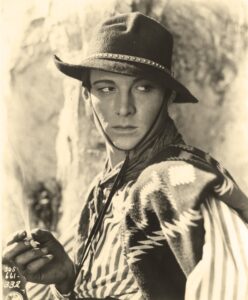

Rudolph Valentino

Like Swanson, the Italian-born Rudolph Valentino—dubbed “The Great Lover”—was unhappy with the way his career was being handled at Paramount’s West Coast studio. In July 1923, he signed a new contract to make films in New York, where he had lived and worked years earlier as a young immigrant who had arrived through Ellis Island. Despite this high-profile move, Valentino only ended up making two films at Astoria in 1924 before another new contract with a different producer brought him back to the West Coast.

D. W. Griffith

Pioneering director D. W. Griffith helped establish Los Angeles as the center for filmmaking in the United States with such elaborate productions as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916), but he enjoyed a greater degree of creative control while based in New York. For Griffith, New York was “home of the best actors, the best artisans, the best and the newest in theatrical production.” Griffith made three films at the Astoria Studio: Sally of the Sawdust (1925), That Royle Girl (1926), both of which feature W. C. Fields, and The Sorrows of Satan (1926).

Louise Brooks

Wichita, Kansas, native Louise Brooks was “discovered” by Paramount producer Walter Wanger while she was a dancer with the Ziegfeld Follies. Brooks began her film career at the Astoria Studio in 1925, making a total of six films for Paramount before moving to Hollywood. She made her two best known films in Germany, Pandora’s Box (1929) and Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), and gradually faded into obscurity. Interest in Brooks’s career and appreciation of her artistry was rekindled in the 1970s. Articles, widely seen photographs, and books—including her own collection of autobiographical essays, Lulu in Hollywood (1982)—cemented her reputation as a fiercely independent, sui generis 1920s icon.

“The stages were freezing in the winter, steaming hot in the summer. The dressing rooms were windowless cubicles. We rode on the freight elevator, crushed by lights and electricians. But none of that mattered, because the writers, directors, and cast were free from all supervision. Jesse Lasky, Adolph Zukor, and Walter Wanger never left the Paramount office on Fifth Avenue, and the head of production never came on the set. There were writers and directors from Princeton and Yale. Motion pictures did not consume us. When work was finished, we dressed in evening clothes, dined at The Colony or ‘21’ and went to the theater. [In Hollywood] to love books was a big laugh. There was no theater, no opera, no concerts—just those god-damned movies.” —Louise Brooks, describing her time at the Astoria Studio

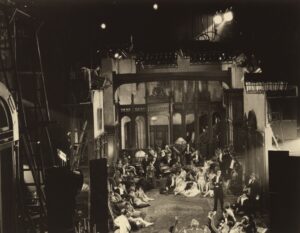

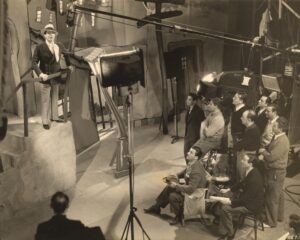

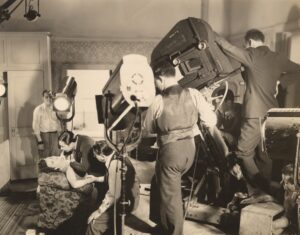

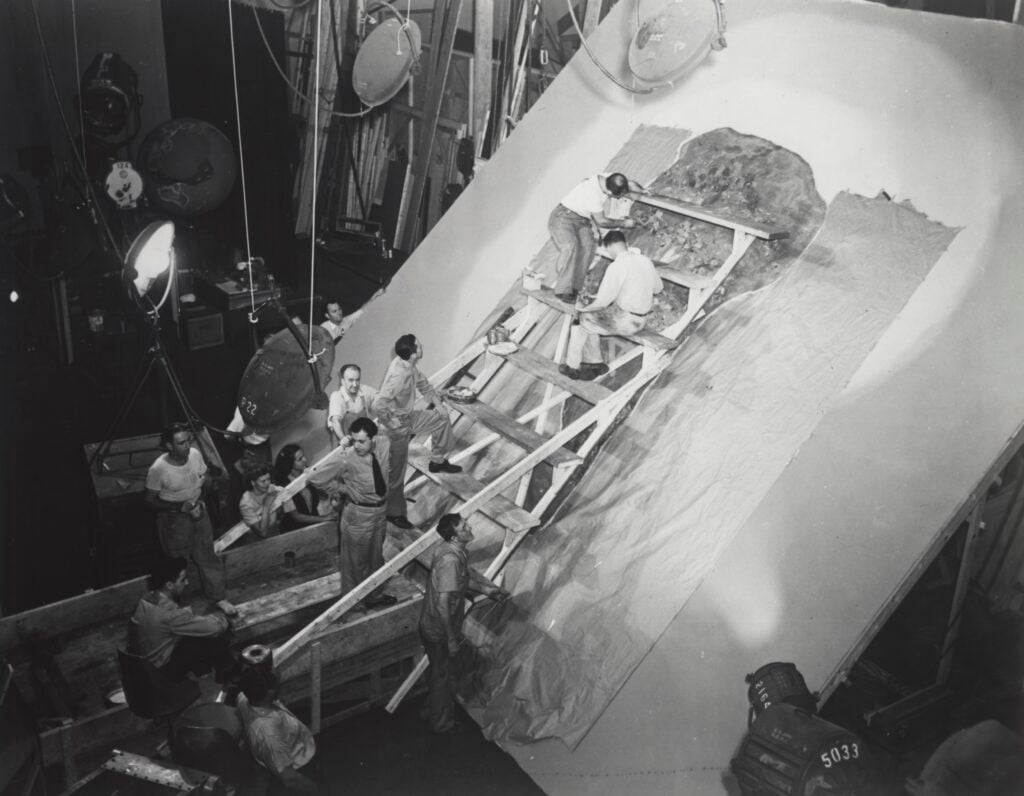

Behind the Scenes at Paramount

The designers, camera operators, technicians, script supervisors, musicians, editors, and others who worked behind the scenes at Paramount’s Astoria Studio rarely received on-screen credit. Only occasionally documented in promotional images, the work of these women and men was instrumental in the production of the hundreds of feature and short-subject films created at the Studio throughout the 1920s.

All but one of the photographs featured here were donated to Museum of the Moving Image by the family of Philip Kandel, who began his career at the Astoria Studio in the 1920s, and remained through the 1960s, when the Studio was known as the Army Pictorial Center.

Paramount: THE EARLY SOUND ERA (1928–1932)

Fourteen months after Schulberg convinced Paramount to shut down production in New York, Zukor changed his mind. The ability to poach actors from the New York theater world was an undeniable selling point with the coming of sound. The transition was rocky, however. Western Electric completed the first Astoria soundstage in July 1928, but the environment was uncomfortable for crew and actors, with its small rooms, thick walls, awful heat, and lack of air conditioning, and because of the tight spaces, the camera could barely move. Paramount eventually installed both sound-on-film and sound-on-disc recording systems, a multi-lingual production center for foreign exports, and by early 1929, new soundproofing, soundstages, and multiple audio channels. By summer, Astoria was averaging a feature a month.

Thanks to the extraordinary talent coming to work in Astoria—both behind and in front of the camera—Paramount’s East Coast films of the burgeoning sound era would make their mark. Paramount founder Adolph Zukor noted, “Certain types of stories can best be made here in the East on account of the availability of particular types of talent.” The Marx Brothers, Claudette Colbert, Maurice Chevalier, Fanny Brice, Helen Morgan, and Burns & Allen were among those who brought their talent to the Astoria stages in the early sound film era. The next four years saw the production of more than 200 short comedies, talking features, and musicals, including Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause (1929), Jean De Limur’s The Letter (1929), the Marx Brothers’ The Cocoanuts (1929) and Animal Crackers (1930), and Ernst Lubitsch’s The Smiling Lieutenant (1931).

Nevertheless, there was increasing financial uncertainty due to the Great Depression. By the early thirties, Paramount was hemorrhaging cash, and a rumor began to circulate that the Astoria Studio would be closed. Despite a few successes; a buffet of newly minted stars like Ginger Rogers, Miriam Hopkins, and Tallulah Bankhead; and top-flight talent like Preston Sturges and George Cukor at the Studio, Paramount’s best films were being made on the West Coast. In 1932, Paramount left the studio to consolidate its operations in California.

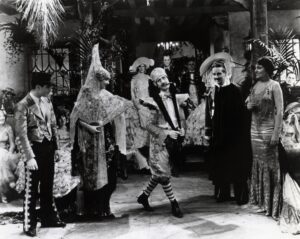

The Marx Brothers

The Marx Brothers were among the biggest attractions of early sound cinema. Already beloved on the New York stage, they first appeared on-screen in 1929’s The Cocoanuts, directed by Robert Florey from a 1925 play written by George S. Kaufman and Irving Berlin. It was a hit despite a difficult shoot, which occurred during the day, while Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Zeppo were back in Manhattan every night performing their latest play, Animal Crackers, on Broadway. The 1930 film adaptation of Animal Crackers, directed by Victor Heerman, would prove a more sedentary affair in terms of filmmaking than the fluid The Cocoanuts, and as a result offered poorer sound recording. Nevertheless, it would also prove a major box office success, marking the Marxes as some of the biggest stars to ever make movies in Astoria.

Eastern Service Studios, Inc. (1933–1941)

After Paramount left in 1932, Western Electric’s ERPI (Electrical Research Products, Inc.) began operating the Astoria Studio as a rental facility. With the goal of marginalizing their chief rival, RCA, ERPI offered independent producers financing in exchange for a commitment to work on sound stages outfitted with Western Electric systems. This investment plan helped to bring Paul Robeson to the screen in The Emperor Jones (1933); allowed noted Hollywood screenwriters Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur the opportunity to direct; and provided work for actors, writers, and producers who embraced the chance to work outside of the Hollywood studio system. Throughout the 1930s the Astoria Studio stages were busy with a mix of slapstick comedies, newsreels, musical shorts known as “soundies,” corporate films, documentaries, and Spanish-language musicals.

Paul Robeson

The Emperor Jones (1933) remains the best known and most acclaimed movie of the independent era shot at the Astoria Studio. Starring Paul Robeson in the leading role, which he originated on-stage, Dudley Murphy’s adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s controversial play follows the journey of Brutus Jones from Pullman porter in the American South to despotic ruler of an African country. The film remains the highest profile screen starring role for the legendary actor and activist Robeson.

Carlos Gardel

Four Spanish-language films featuring Argentine singing star Carlos Gardel were shot at Eastern Service Studios over eighteen months beginning in 1933: El Tango en Broadway, El Dia me Quieras, Cuesto Abajo, and Tango Bar. The heartthrob’s stardom would prove short-lived, as he died in a plane crash in Colombia in 1935 at age 44.

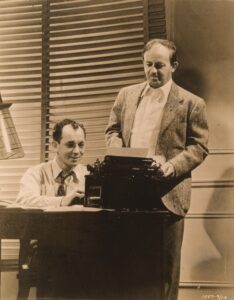

HECHT AND MACARTHUR

Screenwriters Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur took a hiatus from Hollywood, temporarily settling in New York; their first film in Astoria was the hit Crime Without Passion (1934), with Claude Rains as an unscrupulous lawyer. Though mechanically directed by Hecht and MacArthur, Crime Without Passion was expertly shot by Lee Garmes and acclaimed by critics as innovative and economical. Their next film, Once in a Blue Moon (1935), a vehicle for Broadway clown Jimmy Savo, was considered cloying and sentimental, and went unreleased by Paramount for a year, but their next film was perhaps the greatest critical success of Hecht and MacArthur’s independent years: The Scoundrel (1935), starring Noel Coward, which won an Oscar for Best Original Story. Their next and final film made in Astoria, the satire Soak the Rich, was such a flop—the lowest grossing movie of the first half of 1936—that Hecht and MacArthur returned to Hollywood.

THE ARMY YEARS (1942–1970)

Through the 1930s and into the 1940s, Hollywood studios had become increasingly disinterested in making films in New York. The onset of World War II exacerbated the decline of commercial filmmaking on the East Coast, and production on the Astoria stages all but ground to a halt. While the entertainment industry was at least temporarily stalled by the outbreak of war, the U.S. Army, which recognized the value of film as a training and communication tool, was gearing up for production. The cavernous space of the Astoria Studio was perfect for what the U.S. Army Signal Corps needed: a full production center for making training and safety films, as well as entertainments for American soldiers and propaganda films for the American public. By 1945, 2100 men and women were employed at the Signal Corps Photographic Center (SCPC) making movies; during World War II, it was the most prolific movie studio in the U.S. The Army era, which continued in Astoria until 1970, would prove influential on New York filmmaking in general, as many trained there would become professional filmmakers in the coming years, and the methods learned would have an impact on style, skill, and technique in mainstream cinema.

THE SEVENTIES NEW YORK REVIVAL (1976–1979)

New York was on the verge of bankruptcy in the seventies, with neighborhoods throughout the five boroughs feeling the socioeconomic crisis. The Astoria Studio, which the Army left at the beginning of the decade, had become little more than a shell, but by the mid-seventies, union leaders and city officials were instrumental in working with Queens Borough President Donald Manes and Deputy Borough President Claire Shulman reviving the community and helping to restore the building. In 1977, they helped found the Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation, and in 1978 the Foundation successfully campaigned to designate the original Studio building a National Landmark. The Astoria Studio complex would be added to the National Register of Historic Places before the decade was up. As part of the major revival period, the New York State Council on the Arts helped support the restoration of the main soundstage, and several major film productions were shot there, which demonstrated the viability of the Astoria Studio, and set the stage for the major redevelopment of the site by George S. Kaufman, leading to a dramatic and exciting new era for the Studio.

ENTER KAUFMAN ASTORIA STUDIOS (1980–2009)

In 1980, the City of New York awarded the management of the studio site to developer George S. Kaufman. Kaufman, the Studio’s chairman, and Hal Rosenbluth, its president, expanded and modernized the facility—known as Kaufman Astoria Studios since 1982—ushering in a new era of feature film, television, and audio production. Operating independently as a commercial enterprise, with an emphasis on versatility and service, KAS would quickly become a hub for East Coast studio film production as well as an anchor for the rejuvenation of the neighborhood.

At the same time, the Astoria Motion Picture and Television Center Foundation reorganized as the American Museum of the Moving Image, with Rochelle Slovin as its founding director, opening to the public in 1988 in what had once been Army Pictorial Center Building #13. Renamed Museum of the Moving Image in 2005, it houses a permanent collection that includes significant holdings from every era of the Studio’s history. Motion pictures filmed at the Studio have been directed by Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Jodie Foster, Woody Allen, Ron Howard, and Mike Nichols. Television production simultaneously became a mainstay of KAS, including such high-profile programs as NBC’s The Cosby Show; PBS’s Sesame Street, which began its residency at Kaufman in 1993; and Showtime’s Nurse Jackie, starring Edie Falco. Kaufman and Rosenbluth’s complete revitalization of the Studio proves that an historic landmark can live on, continue to change, evolve, and grow with rapidly changing times.

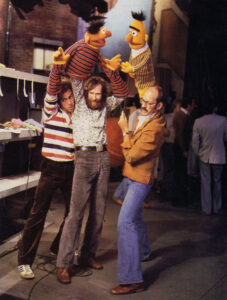

SESAME STREET

In 1993, Kaufman Astoria Studios welcomed its most exciting long-term resident. After 24 years of being filmed in Manhattan, Sesame Street picked up and moved to Queens, where KAS offered more space for the ever-expanding universe of the children’s educational television classic. Ever since, Astoria has remained home base to the show. Today, the neighborhood of Big Bird, Oscar the Grouch, Elmo, Abby Cadabby, Bert, Ernie, and all of their human friends feels essential to Queens, and has come to represent a microcosm of the beautiful diversity of the borough as a whole.

THE MODERN ERA (2010–present)

In 2010, Kaufman opened Stage K, a 40,000-square-foot stage located across the street from the original building. A studio backlot opened in 2013 and a new building housing two additional soundstages opened in 2019, bringing the Studio’s total to twelve stages. Today, Kaufman Astoria Studios is one of the preeminent production facilities in the country. The Studio has remained home for New York entertainment, including popular shows on streaming giants like Netflix (Orange Is the New Black) and Apple (Dickinson), as well as instant classic contemporary movies like Birdman and The Irishman. Alongside Museum of the Moving Image next door, and the Frank Sinatra School of the Arts, founded by Tony Bennett, directly across the street, Kaufman Astoria Studios is a continued reminder that western Queens remains a motion picture capital of the world.